Do I Really Always Need Healing?

|

"Healing" seems to be the primary or even solitary spiritual metaphor these days. Sermons, book titles, seminars, YouTube talks, etc. are fixated on spiritual and psychological healing:

The implication is that I am sick, broken and fundamentally defective.

First off, let me acknowledge that healing is a legitimate metaphor when referring to psycho-spiritual traumas, but it is not the only symbol for approaching emotional distress--nor perhaps even the best. When the healing metaphor fails, I am stuck without alternative ways of seeing my trauma. There is another metaphor found in Carl Jung's autobiography:

"It has always seemed to me that I had to answer questions which Fate had posed to my forefathers and which had not yet been answered, or as if I had to complete, or perhaps continue, things which previous ages had left unfinished." (Jung, Memories, Dreams and Reflections)

Here Jung sees his psycho-spiritual

problems, not as inherited family illnesses, but as congenital "questions posed by Fate" to his ancestors. In this view, my ancestral connection has passed along the assignment to for me to take up. Here Jung uses a developmental metaphor in order to emphasize the soul's ongoing process of continuation and completion rather than that of inflexible sickness and brokenness. In a developmental metaphor, trauma is more like an algebra assignment. I am not broken and don't need to heal anything, but am allowed to continue working on and completing the Fateful family assignments. problems, not as inherited family illnesses, but as congenital "questions posed by Fate" to his ancestors. In this view, my ancestral connection has passed along the assignment to for me to take up. Here Jung uses a developmental metaphor in order to emphasize the soul's ongoing process of continuation and completion rather than that of inflexible sickness and brokenness. In a developmental metaphor, trauma is more like an algebra assignment. I am not broken and don't need to heal anything, but am allowed to continue working on and completing the Fateful family assignments.

Jesus and the Apostle Paul frequently use developmental agricultural images to symbolize the spiritual life:

Many early Christian theologians viewed Adam and Eve--planted like human seeds in the Garden of Eden--as a parable for human development. The so-called "fall" denotes the moment the embryonic human is cast into the soil of life in order that each of us might move from the raw image of God into the completed likeness of God. In this view, I don't need healing, but rather maturation through ongoing life experiences--negative and positive.

But when healing is my sole symol for spiritual and psychological traumas, I assume

the only alternatives are to get well or remain sick. If I don't "get well," then I have failed and remain sick and broken. But the educational and agricultural developmental metaphors allow for progress through the ancestral journey. I am merely one student in a family endeavor. I am not defective, but merely incomplete until the assignment is finished--likely many generations from now. the only alternatives are to get well or remain sick. If I don't "get well," then I have failed and remain sick and broken. But the educational and agricultural developmental metaphors allow for progress through the ancestral journey. I am merely one student in a family endeavor. I am not defective, but merely incomplete until the assignment is finished--likely many generations from now.

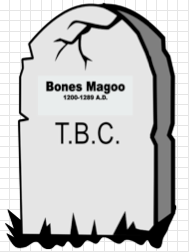

When it comes to psycho-spiritual traumas, let's utilize our metaphorical imaginations. Life is more than a disease to be healed, much more than the mere cessation of all suffering. It is a vital journey through many stages and modes of being and living. Perhaps instead of R.I.P. ( Rest in Peace ) on our gravestones, we ought to etch the letters T.B.C. ( To Be Continued ).

Michael

|